Features

Breeding

Technology

Orkney Shellfish Hatchery thinks inside the box

Scotland hatchery is on a mission to save and restore populations of European native flat oysters

April 30, 2021 By Liza Mayer

Dr. Nik Sachlikidis, managing director for aquaculture, Cadman Capital Group All photos: Orkney Shellfish Hatchery

Dr. Nik Sachlikidis, managing director for aquaculture, Cadman Capital Group All photos: Orkney Shellfish Hatchery Snorkelling through the coral gardens of the Great Barrier Reef and discovering marine life was normal for most kids growing up in Cairns, Australia, like Nik Sachlikidis. Early exposure to the need to care for and conserve the world-famous natural wonder made such an impact on him that aquaculture as a career choice became a no-brainer.

“Everything below the waves interested me,” says the managing director for the aquaculture portfolio of the U.S.-based Cadman Capital Group. Sachlikidis progressed in aquaculture from the ground up, beginning as a teen working on fish farms in North Queensland.

Earlier in his professional career, he held a range of scientific leadership roles in industry-science partnerships focused on the development of lobster aquaculture techniques and technology. “I worked my way as a researcher for the government, through to private enterprise in Southeast Asian aquaculture and then eventually over to the Cadman Capital Group,” he says.

The multinational private equity group’s aquaculture division comprises three core businesses: Caribbean Sustainable Fisheries, a fully operational spiny lobster farm in the British Virgin Islands; Orkney Shellfish Hatchery, a multi-species shellfish hatchery focused on the cultivation of European native flat oysters (Ostrea edulis) and European clawed lobsters (Homarus gammarus); and Ocean On Land Technology, an innovator in aquaculture systems technology.

Group founder and chairman Giles Cadman says his passion for sustainable aquaculture led him to enter the field. The Group’s first venture into aquaculture, Caribbean Sustainable Fisheries, “exists because I believe that entrepreneurs have to ‘walk the talk’ when it comes to preserving the environment, helping local communities and helping each other,” Cadman writes on his blog.

That mission is what guides Orkney Shellfish Hatchery (OSH), located on the small, uninhabited island of Lamb Holm in Orkney, Scotland. The hatchery, or “Osh” as the staff calls it, is designed to help restore the population of native European flat oysters, wiped out because of overfishing throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. The facility is also meant to demonstrate the technical and economic feasibility of tech innovations, such as the Hatchery-in-a-Box, an alternative technology to growing clawed oysters (see side bar).

A 2019 report from Scotland’s Centre of Expertise for Waters (CREW) makes the case for the restoration of the population of the native flat oyster: “The single advantage that the native oyster has over other shellfish with more established production (for instance, the common mussel) is in its ecological, cultural and social value. Unlike the Pacific Oyster Crassostrea gigas, Ostrea edulis is a native and therefore its restoration is likely to enhance, and not to damage, ecosystems. Emotionally, it has a popular appeal as a missing ecosystem from Scotland’s coastal water.”

OSH clearly sees the opportunity to fill this need. The native flat oyster currently accounts for only 0.2 per cent of Scotland’s shellfish aquaculture, eclipsed by the faster growing non-native C. gigas (4.5 per cent), and even more so by mussels (95.4 per cent), data from the CREW report show.

“We want to be a key player in the development of native oysters in the U.K. and an enabler for those restoration projects that are going to enhance those native environments,” says Sachlikidis.

Trump cards

OSH’s progression into playing a role in Scotland’s restoration efforts followed the same ground-up trajectory, beginning with the choice of the hatchery site. OSH operates in the most northern part of Scotland, its remoteness providing biosecurity and access to pristine seawater, he says.

“It has given us a biosecurity moat. When one is looking at things like native oysters and other things, one of the main problems is the disease issue for broodstock oysters. Orkney is a place that’s designated as Bonamia-free, which is one of the pathogens that’s impacting the native oyster populations.”

The former hatchery structure had done some work on oysters and lobsters in the past but it was non-functional when the Group acquired it three years ago. “We did a major overhaul of it. The team at Ocean On Land Technology (the same team behind Hatchery-in-a-Box) did a great job renovating the whole site and providing the technology, including the recirculating aquaculture systems and other technology for oyster rearing,” he says.

Now a fully-fledged hatchery building, it features innovative biosecurity systems that control the movement and spread of harmful biological agents both within the hatchery and between the hatchery and the surrounding environment.

Aside from implementing strict movement protocols, the team also has access to specialized equipment. “Broodstock wastewater is treated with a three-step process of micro-filtration followed by ultraviolet filtration and chlorination/neutralization to kill potential pathogens such as viruses and bacteria. Together, these measures integrate successful oyster culture with the safeguarding of the surrounding waters,” OSH said in an earlier statement detailing its progress.

In late 2020, OSH installed a secondary wastewater filtration system designed to treat all of the hatchery’s wastewater for potential pathogens before discharge.

“It provides a substantial barrier between the OSH hatchery and the outside environment. Our hatchery treats all outgoing wastewater through a series of fine filtration and heavy UV treatment to destroy any potential pathogens. This means that the hatchery is bio-secure on both the incoming and outgoing seawaters,” Sachlikidis emphasizes.

The strict protocols and the hatchery’s decision to propagate only the native flat oyster species have set OSH apart from others in the market. A private-sector initiative called the Dornoch Environmental Enhancement Project (DEEP) has taken notice.

In the CREW report, DEEP expressed interest in making OSH a part of its supply chain for native oyster spat that will be planted in 40 hectares of native oyster reef targeted for restoration.

“DEEP is interested in working with OSH as part of the supply chain due to the biosecurity aspect of the hatchery. Existing hatcheries that produce both Pacific and native oysters are not able to ensure that the native oyster spat is not commingled with Pacific oyster spat, an invasive non-native species (that) must not be introduced to the DEEP or other restoration sites,” it said.

Gaining ground

OSH has made headway since moving broodstock from an offsite quarantine area to the hatchery in August 2020. The broodstock successfully fed on a mixed diet of live algae harvested from the two large photo-bioreactors at the hatchery, “clearing more than 80 per cent of their feeds overnight and indicating that they have settled into their new system,” announced OSH that month.

This past October, it saw its first run of native flat oysters production. “We’re at the point now of commercial upscale for production of edulis. We can now start taking on clients and making those arrangements to supply them with oyster spat for the 2021 seasons onward,” Sachlikidis tells Hatchery International.

The quest to further refine their technology to produce “super high-quality” edulis spat remains on the agenda. “Our milestones are improved production capacity and upscaling this year and bringing on some of that technology – we’re looking at our genetics in our broodstock as well. We’re going to incorporate some eDNA technology to make sure our spat are of the highest quality, we’re working on some DNA screening technology to make sure we’re on the cutting edge of that,” he says.

“Our goals are to produce those big numbers of edulis that restoration programs and indeed farmers can rely on and be able to confidently restock in their waters or on their farms. That would be just a fantastic thing not only for our hatchery but for the ocean itself.”

Technology test bed

Aside from supporting the restoration of the European native flat oysters in local waters, Orkney Shellfish Hatchery’s (OSH) role is to serve as a resource to test new hatchery ideas and technology, including the Hatchery-in-a-Box (HIB), a complete hatchery solution that requires a fraction of the footprint of a conventional hatchery.

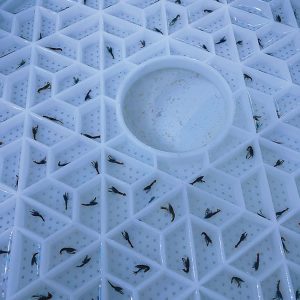

Hatchery-in-a-Box is a 40-ft., portable sea container that’s fully insulated and temperature-controlled, and incorporates hatchery fundamentals. Among these are Ocean On Land’s flagship technology, Aquahive, which houses small post-laval lobsters in a patented bee-hive-like container to prevent the cannibalistic juvenile lobsters from eating each other.

“It’s really an all-in-one solution in that it’s a shipping container that you put on the ground and it’s got everything you need within it including the RAS systems to produce the lobsters,” says Nik Sachlikidis, aquaculture managing director of Cadman Capital Group.

Explaining the setup, Sachlikidis says lobster eggs are hatched in a broodstock container that has a larval rearing capability, and “once they’ve become post larvae, they get transferred into the Aquahive technology where they’re grown to Stage 5/Stage 6, which is a very robust juvenile, and then they can be released for grow-out.”

One Hatchery-in-a-Box is designed to produce around 50,000 juveniles a year, but in January, the hatchery team at OSH got an unexpected result that potentially could boost this number: they saw the first lobster hatchings for 2021 in January, which is much earlier than the expected March “due date.”

Sachlikidis attributed the good news to a series of conditioning of the broodstock, as well as to the broodstock holding system that the team could manipulate to achieve optimal temperature and environmental condition.

“We were therefore able to bring the season forward. We were able to get regular hatches, in Orkney, for this species for at least 10 months of the year, which is substantially more than in their natural timing. There’s some real advantage to that because we’re able to keep the scale of the hatchery small but produce on an elongated timeline that helps us with capital investment per unit of production.” In other words, one unit of HIB could potentially produce more than the annual 50,000 lobsters expected.

The next step in terms of the HIB technology is to develop a bigger version that’s able to grow the juveniles from Stage 6 to grow-out. In this effort, the Ocean On Land will lean on its sibling “Osh” to test it and showcase a working Hatchery-in-a-Box to give potential users a real-time look at how the technology works.

“Clawed lobsters are a very commercially important species in the U.K. and the rest of the world. We want to support those fisheries and make sure that they are alive and healthy and have the technology they need to continue to be that way,” says Sachlikidis.

Print this page